COVID-19 has stifled economic activity, leading to a drop in carbon emissions and clearer skies. But don’t count on the pandemic saving our planet.

Could lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic spur world leaders into more effective action to tackle the biggest threat facing our planet – climate change?

This is a question worth pondering four months into a crisis of a scale not seen in more than a century. Since the first case of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, was discovered in China, the virus has raced around the world with astonishing speed, sickening people in 187 countries.

As of writing, the virus has infected 3.5 million people and killed 248,000. In the United States, the country with most cases, the death toll has raced past the 58,000 Americans who died in the Vietnam war, according to data tracked by by Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering.

No end is in sight to the spread of the virus, and so far there is neither a cure nor a vaccine. But restrictions that have locked millions in their homes, shuttered businesses and required people to keep physical distance have reduced the rate of new infections in several countries.

Germany, Denmark, Norway, the Czech Republic, Poland, Switzerland, Albania and Greece have taken small steps towards relaxing their lockdowns and re-opening some businesses. Others – Russia and Britain – have tightened stay-at-home rules.

In the United States, where shut-downs have resulted in 30 million workers losing their jobs, 33 of the country’s 50 states have taken steps — some small, some big — to relax restrictions on business and social life by early May.

There are few doubts that the COVID-19 pandemic will eventually end, as did the plague in the Middle Ages and smallpox in the 20th century, but there is no end to the effects of climate change on our planet, described by United Nations scientists as “the defining issue of our time.”

The coronavirus and climate change have a catchphrase in common: “We are all in this together.”

But are we really?

COVID-19 has revealed a lack of international cooperation.

Once the global threat posed by the coronavirus became clear, the default reaction across most of the world was to close borders, as if the virus respected national sovereignty. Next came a cut-throat international scramble for medical equipment, from ventilators to face masks and gloves.

While the United States came under much criticism for outbidding other countries and even intercepting shipments destined for others, global solidarity was lacking elsewhere, too. Several European countries banned the export of medical equipment to make sure they had enough for their own citizens.

The fumbling, disjointed initial response to the COVID-19 virus and the dearth of coordination among world leaders — with a few notable exceptions — raised questions about international preparedness for tackling climate change and its effects on the planet.

While the virus’s race around the world has been felt viscerally, the climate crisis is playing out on a much slower time frame, said one of America’s top climate scientists, Peter de Menocal of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, the laboratory that first came up with the concept of global warming.

“We know roughly what to expect and when to expect it,” he told the New York Times, “and we should be preparing with the same level of urgency.”

After COVID-19, there will be a rush to grow economies.

That is not happening. Fighting climate change not only requires political will and international coordination but also substantial government spending. Once COVID-19 is tamed, there is no doubt that the first priority of governments around the world will be to rebuild economies shattered by lockdowns. Saving the planet will not be high on the list.

The International Monetary Fund has predicted the global economy will experience its worst recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s, more severe even than the deep slump that followed the Great Recession of 2008.

The gloomy background may well amplify the voices of experts and politicians who point to a long string of meetings and international agreements over the past three decades that have failed to curb carbon emissions, the primary reason for global warming.

A clean planet after COVID-19 would require a fresh approach.

Among the many reasons for the failure to clean up the planet: the benefits of decisive action lie in the future but the costs are present — and run into armies of lobbyists with enormous political power, representing industries that contribute to pollution.

Another obstacle on the way to a clean planet is the structure of the international agreements to fight climate change. As Yale University’s William Nordhaus, winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics, put it, climate meetings under the umbrella of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change have been marked by “a total disconnect between the need for sharp emissions reductions and the outcome of deliberations.”

In an essay in Foreign Affairs, a monthly magazine closely read by America’s foreign policy establishment, Nordhaus said that the central flaw of the present architecture is that agreements reached through it are voluntary, prompt free-riding and therefore fail.

He suggests establishing a “Climate Club” that would slap penalties – tariffs, for example – on countries that failed to meet their obligations.

Clearer skies, yet climate change deniers persist.

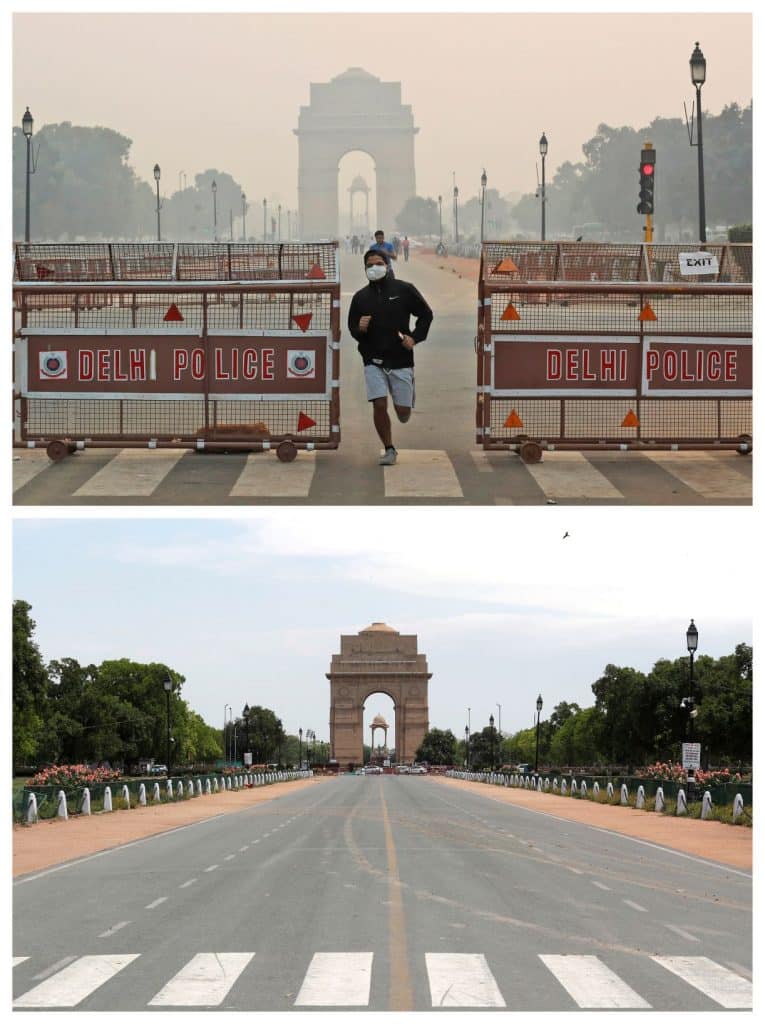

Oddly, the sudden halt to economic activity caused by COVID-19 has produced stunning demonstrations of what the planet would look like if climate targets were reached. Of a series of pictures taken before and after shutdowns, one stands out.

It shows the India Gate memorial in New Delhi, the world’s most polluted city, in October 2019 and again in April 2020. In October, the monument was barely visible, obscured by light-brown smog. The later photo shows the ochre-colored arch in fine detail. The contrast is stunning.

Whether that would change the attitude of climate change deniers such as U.S. President Donald Trump or Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro is in doubt. Both have described climate change as a hoax, and both are working to torpedo progress.

In the United States, the world’s second biggest emitter of carbon dioxide after China, Trump has been rolling back a long list of regulations protecting the environment. In Brazil, Bolsonaro is encouraging burning or hacking down the Amazon rain forest — deforestation in the name of economic development.

Neither of the two will be in office forever. But as long as there are leaders in their mold, the outlook for a healthy planet is bleak.

(For more stories on COVID-19, click here.)

THREE QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

- How would you characterize the international reaction to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus?

- In your view, why have efforts to curtail global warming failed so far?

- Do you think that the sacrifices that people around the world have had to make during the COVID-19 pandemic will make it easier for them to change their behavior in order to save the planet?

Bernd Debusmann is a News-Decoder correspondent and former columnist for Reuters who worked as a correspondent, bureau chief and editor in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and United States. He has reported from more than 100 countries and lived in nine. He was shot twice in the course of his work – once covering a night battle in the center of Beirut and once in an assassination attempt prompted by his reporting on Syria.